Challenging violence against women in real life requires challenging the way it is often glamorized or trivialized in fiction. Equation’s Reel Equality volunteer, Sarah, explores the casual infliction of violence against women in Hollywood through a review of Marjane Satrapi’s The Voices.

Please note: this review contains some descriptions of brutal violence.

We are not even half way through 2015 and already it has been a year of extremes for women in film. On one hand, the women of Hollywood are fighting for their rights by shouting out for equal pay in the film industry (Patricia Arquette at the Oscars). However, it’s almost as if they are being punished for having a voice as those actresses are being whipped, gagged, and literally chopped up at the mercy of male protagonists in films they are given to star in.

I think we all know the recent behemoth in the cinema which overtly promotes such sadism. Released on Valentines Day, 50 Shades has made more than $500 million at the global box office. Yet, 50 Shades of Grey is an obvious a choice when talking about glamorising violence against and control of women in cinema. What we really need to start commenting on is all of the other, more subtle ways in which Hollywood cinema cuts, whips and chains actresses to one-dimensional, stereotypical roles.

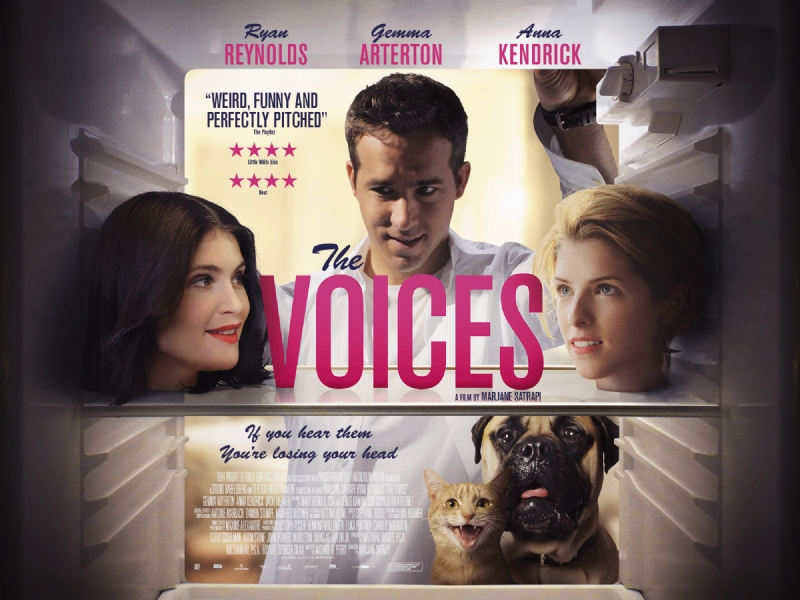

Recently released dark comedy, The Voices, starring Ryan Reynolds, Gemma Atherton and Anna Kendrick does precisely that as it attempts to make light of a misogynistic, murderous schizophrenic. Reynold’s character, Jerry, appears mild-mannered, if not a little carnivorous, at the start of the film. The delightful pink overalls he wears for work allow him to appear in touch with his “feminine”, soft-centred side.

The film has a distinct essence of the horror genre, only our villain is likable and ‘understandably’ troubled, allowing audiences to sympathise with his destructive thoughts. Frequent homages to classic horror death scenes are depicted – the women victims are brutally punished for their sins by being chopped up, preserving the only body parts which men should care about.

Hollywood cinema is obsessed with reducing women down to their appearance and The Voices is certainly no exception. There is a considerable amount of focus on the women’s bodies in the film, especially as they meet their death. For both love interests Fiona (Gemma Atherton) and Lisa (Anna Kendrick), the camera pans over their bodies in a close up which serves to sexualise their deaths as they lie paralysed and totally at the mercy of Jerry for the audience’s visual pleasure.

Poignantly, it is the heads of the women which Jerry preserves. With their bodies discarded, every feature of their appearance remains unblemished. Hair tousled, make-up freshly applied, expressions excited and friendly; these women clearly enjoyed being beheaded and nothing has changed now they no longer have a body. They have no problem with serving Jerry’s needs because they are his fantasy.

In reality, they are dead and rotting in his fridge, but to Jerry’s – and the audiences’ – perspective, these women want to serve him and make him happier. These heads represent an idealised for of womanhood from the perspective of the man; an unblemished fantasy – perfect, beautiful and without opinion of the mutilation which occurs to their bodies.

Not only does the film bear witness to the chopping up of women’s body parts, but it actively encourages and laughs at it. Much of the source of the “humour” from the film comes from the foul-mouthed cat, Mr Whiskers. This ‘voice’ is the one who pushes Jerry to want to commit the murders, and then praises him for doing so. And so, yet again, the comedy is made at the expense of the woman as a result of Jerry’s apparently hilarious delusions.

These men’s voices suggest that it is okay for violent desires to be acted out on women as there is no moral repercussion for having misogynistic thoughts or desires.

While Jerry feels remorse and guilt for the murder of his love interests, his final murder is the one that personally really rattles my bones. When a work colleague, Alison (Ella Smith), visits Jerry to see if he knows anything about the whereabouts of Lisa, her fate is sealed by a brutal slashing noise and a cut to her dismembered head. Although she is just as intelligent, caring and funny as the other young women, Jerry shows no remorse for murdering the woman who he has no sexual desire for.

This is especially upsetting when we consider the bigger picture of the ideal woman’s body in Hollywood. Alison subverts the norm because her body is considerably larger than her women counterparts. And it is her who is killed without reason. She is punished for having a body which is out of the norm, out of control and so not even the affections of Jerry can delay her murder. The film effectively fat-shames her. Even as a disembodied head, she is allowed a voice to agree with the ‘beautiful’ women.

I can’t help but feel disappointed by Marjane Santrapi’s move into Hollywood. The film’s dark humour does have to be taken with a pinch of salt, but it does nothing to challenge the massively unequal status quo of women in film. Her women’s characters are shallow, one-dimensional and become victims for highly typical reasons. The violence inflicted upon women in cinema is already normalised, and this film only perpetuates the notion that it is perfectly fine to cut women up and cut them down.